By John W. Fountain

My wife was simmering with indignation, holding the newspaper she had just retrieved that morning a few years ago from our mailbox—the newspaper I had written for as a freelance columnist for the previous seven years. “Hmph, will you look at this…”

I looked at the front page, eager to see the object of her anger. There it was, an above the banner header. The faces of the newspaper’s top columnists: Eight white men, three white women, one black woman. No black men. No not one.

No John Fountain.

An all-star opinion writer’s line-up, it was anchored by the moniker: “The voices of Chicago. …They’ll get you talking.”

"The more I reported and wrote the more I could hear in my own writing the chorus of voices too often forgotten, neglected or ignored by the mainstream press..."

|

| John Fountain and former student Mario Parker show off Lisagor Awards for journalism. |

I explained to my wife—herself a journalist with a passionate pen—although to no complete satisfaction, that the columnists pictured were full-time staffers and I was a mere freelancer. She said she understood but wondered how, among the “voices of Chicago,” I would not also be counted among them—notwithstanding the fact that there are plenty of writing heavy-hitters in this city.

Indeed I am humbled to be among the opinion writers today in Mike Royko’s town, in this also the city of the late-, great, Studs Terkel whom I had the honor of meeting some years ago when we both read our essays for a local release event for National Public Radio’s “This I Believe” book.

I grew up reading Royko in the Chicago Sun-Times, climbing aboard the CTA bus on the morning ride to school and turning to the sports pages first, then straight to Royko. He was blunt. He was funny. He made me laugh. He made me think. Made me feel.

|

| Chicago, John Fountain's hometown. |

I was drawn to commentary. To other voices: Lu Palmer. Warner Saunders. Vernon Jarrett. Unflinching, honest and insightful they were. Voices of Chicago? Even for these journalists—all of them black men—that would depend on which “Chicago” one was considering.

But these particular voices spoke to my Chicago. In them, I heard—and I saw—myself. I felt anger. I felt justification. I felt recognized. I felt finally visible.

Years later, while in journalism school at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where I earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in journalism, I read Leanita McClain’s “A Foot in Each World.” The former Chicago Tribune columnist whose machine-gun precision and passion leapt from her writings ignited my writer’s soul. She made me cry. She made me applaud. I craved Leanita’s ability to be brutally honest as well as her lyrical expression of razor-blade truths that were a double-edged sword.

For years as a reporter, I dabbled in commentary, writing a piece here and there, but mostly tucking away my private thoughts on matters public and private far from publishing view. As a young reporter at the Chicago Tribune, I often entertained the idea of becoming a columnist someday. But frankly, I was overwhelmed by the idea of regularly writing commentary and didn’t think at the time that I had that much to say. That I hadn’t yet lived enough life.

I went on from the Tribune, where I honed the nuts and bolts of reporting as a night-side general assignment reporter, then to suburban beat reporter and later as the newspaper’s chief crime reporter. I went on cut my teeth as a reporter at the Washington Post and later at the New York Times. At the Post, for years I dug in as a reporter, drawn to stories about the victims of gun violence, to stories about poverty and the poor. Drawn to themes like social justice, fair housing, education, equality, race and hyper-segregation, even hopelessness and any story that allowed me to explore the human condition, to capture the story of our collective humanity regardless of race or class.

|

| The American Millstone ran initially as a series in the Chicago Tribune in 1986 and focused on life in the West Side's North Lawndale. |

The more I dug, the more funerals of children I covered, the more I spoke to mothers and fathers and grandparents about the pain and suffering of having lost someone to murder. The more time I spent reporting in Chicago’s housing projects—habitats, in some cases, not fit for animals let alone humans. The more I chronicled the stories of people who most often did not grace the pages of the newspapers I worked for over a 30-year career.

The more I reported and wrote the more I could hear in my own writing the chorus of voices too often forgotten, neglected or ignored by the mainstream press, unless they were too often being painted in broad strokes and harsh stereotypical tones that tend to do more harm than good.

The Tribune’s “The American Millstone” series in 1986, on the West Side’s North Lawndale is a classic, though hardly unique, example.

“A new class of people has taken root in America's cities, a lost society dwelling in enclaves of despair and chaos that infect and threaten the communities at large,” the commentary for the series begins.

“…Its members don't share traditional values of work, money, education, home and perhaps even of life. This is a class of misfits best known to more fortunate Americans as either victim or perpetrator in crime statistics.”

They were “the millstone”—the weight of affliction draped around America’s neck. Except I was one of them. Born in North Lawndale, I was there—young, married, in my early 20’s, on welfare and struggling to survive and in college with a family—when the Tribune’s reporters came looking for the story.

I could have told them a different story, shown them a different side. My sense has always been that that’s not what they were after. A few years after the series, when I entered the Trib’s newsroom as a full-time staff reporter, my very presence did prove a different side to the North Lawndale story. But I suspect they were still too blind to see—no room for perspectives that lie beyond the boundary of their jaded white-washed paradigm.

My voice and my passion as a writer, my writer’s eye, have led me to seek to tell for a career now the stories of life on the other side of the tracks. Caused me to gravitate toward the “Cold Coast” instead of the Gold Coast, even as a columnist over what has now been the last 12 years.

I have learned lessons along the way. Perhaps none greater than this: That in journalism—whether as independent objective observer or commentator—the story is never about you. That at the beginning or the end of the day, it really isn’t about winning awards, although awards are certainly nice.

That it isn’t about accolades or gaining journalism celebrity. Not even about whether my mug—rightly or wrongly—does not appear with other esteemed writers in this my hometown. Not about whether mine is ever deemed to be a “Voice of Chicago.”

Truth is, that has never been my aim as a writer. I want to be a voice for the poor, for the downtrodden, for the invisible, for the forgotten. For the voiceless.

For the black men who sometimes stop me on the street and say, “Thank you, brother. You speak for me.” For the mother of two murdered children who says that my voice has provided “comfort, inspiration, and empowerment.” For the elderly Black ladies who say they clip my columns and save them. Or those who say they post them on their refrigerator or note boards at work, or send them to out-of-state relatives.

I explained all this to my wife. I explained that it still doesn’t diminish the sting. But that nothing compares to knowing that my words have made a difference.

My pen, my words, my voice used to the glory of God, for the benefit of others, even the least of these. A Chicago voice—bred, born and raised right here in the Chi, in a place called K-Town. Facts.

And it just doesn’t get any sweeter than that.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

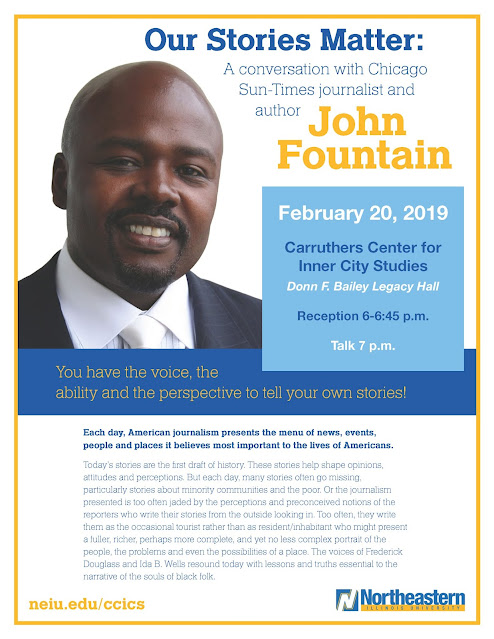

|

| A flyer from a presentation by John Fountain speaks to his philosophy on journalism and the need for marginalized people to tell their own stories. |